Raptors occupy deep, sequestered recesses of the human psyche, harkening back to a time before our knuckles left the ground, a time when our species’ survival was dependent upon a visceral knowledge and understanding of the natural world around us. Raptors patrolled that world from the air carrying their lethal weapons, beak and talon, with them in their ceaseless search for prey, and the night watchers among them, the owls, spread mystery and mayhem on silent wings even in the dark of night. Those who came before us knew well those we now call raptors.

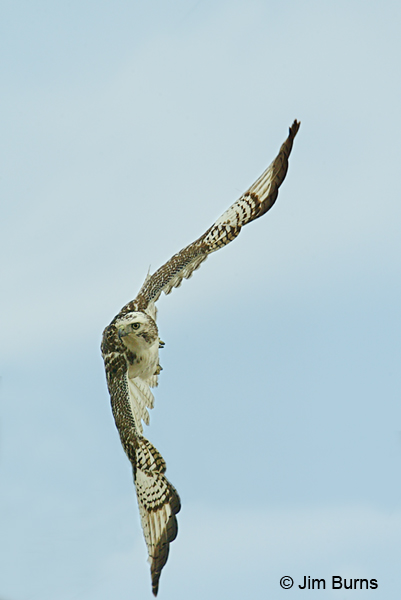

Yes, the beauty of raptors in flight is arresting and awesome, the full spread of the ventral wings as they soar, bank, and dive above us, long primaries like fingers in the wind, conjure up our atavistic longing for flight itself and the freedom it would bring to go wherever we wanted to be. Nonetheless, everyone I’ve ever questioned about the appeal of raptors begins or ends with their residence at the top of the avian food chain. Raptors are birds of prey, exquisitely evolved to kill and eat other animals.

Since the beginning, humans have viewed birds of prey with envy and awe, admiring their power, ferocity, and aerial agility, well aware of their keen eyesight, sharply curved beaks, and lethal talons, compelled to learn from and try to mimic their survival instincts. Raptors were “charismatic avifauna” before that term, and writing itself, were a thing. And now, as we have lost much of our connection to nature, raptors serve as a reminder, a spark, a rekindling, almost a guilty pleasure.

I cannot not photograph every raptor I see, this despite already having hundreds of fine images of some of our most common—Great Horned Owls, Red-tailed and Cooper’s Hawks, and Bald Eagles. Imagine, then, how my head exploded in recent years with my first opportunities to finally get photos of a Northern Pygmy-Owl in snow and a Merlin catching dragonflies, images I had never even visualized as possible.

Post-pandemic, as our birding adventures have focused on less common birds that we have not seen often or well over the years, we have made dedicated trips specifically for Golden-cheeked Warbler and for long-time nemesis bird, Ruffed Grouse. Despite the visual and photographic success on both those target species, unexpected raptors stole both shows. In the Texas hill country looking for the former, we chanced upon a Krider’s Red-tail, a first for me. In Minnesota’s Sax-Zim Bog searching for the latter, I got long-hoped for images of the beautiful dark morph of the Rough-legged Hawk. Raptors, then, were the best birds of both trips.

Top of the food chain indeed! Imagine if humans could capture, dispatch, prepare, and then eat other animals without the use of external tools, using only their own physically evolved body parts: keen eyesight to discern distant prey; speed of flight for the chase; tomial teeth for the killing; strong feet with needle-like talons for gripping and transporting; sharp, pointed beak for shredding.

No avian species except the raptors, and certainly no earthbound species at all, exhibit so many features humans admire and desire. We are but flightless raptors residing at the top of our grounded food chain, but flight remains the dream.